One of the more surprising things I’ve discovered as an artist is that a particularly satisfying thing to with ancient artworks and priceless ceramics is to destroy them.

I’m talking figuratively, of course. Conscience and reinforced glass cabinets prevent me from putting this impulse into practice. But I feel that shattering historical artefacts in the imagination and scattering the remnants in coloured pencil creates a special way of engaging with them.

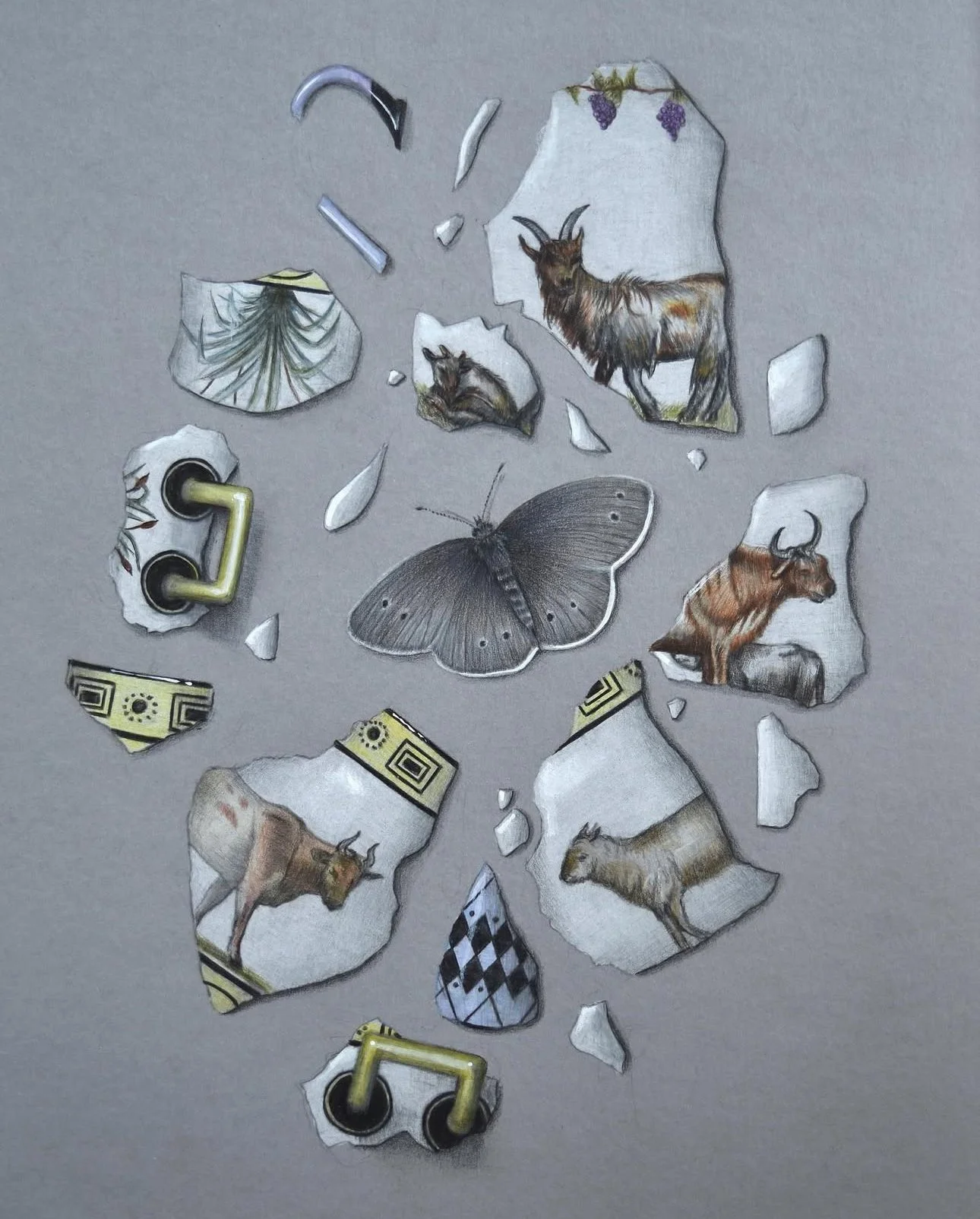

In the case of pottery is allows us to do something that the laws of physics would otherwise prevent: directly view two sides of a curved surface simultaneously. This is something I explored in a commissioned still life of two eighteenth century Sèvres porcelain cups, part of the so-called ‘Etruscan’ set made for display at Marie-Antoinette's Dairy at Rambollillet.

Photo courtesy of Gabriel Wick

In real life the cups are fortunately intact. But shattering them in my imagination and scattering the pieces on the flat surface of the paper meant the images on them were no longer part of the cups’ decorative schemes.

Now, with cows, a sheep, a goat and various pieces of foliage jumbled and out of context, they were connected not by an unbroken curve but by whatever associations came into the mind of the viewer.

Moreover, the fact that these fragments took the form of a drawing, and were therefore relegated to the world of a single dimension, meant that they could not be picked up or pieced back together. In some sense, then, they were no longer the fragments of a whole, but a complete piece in their own right.

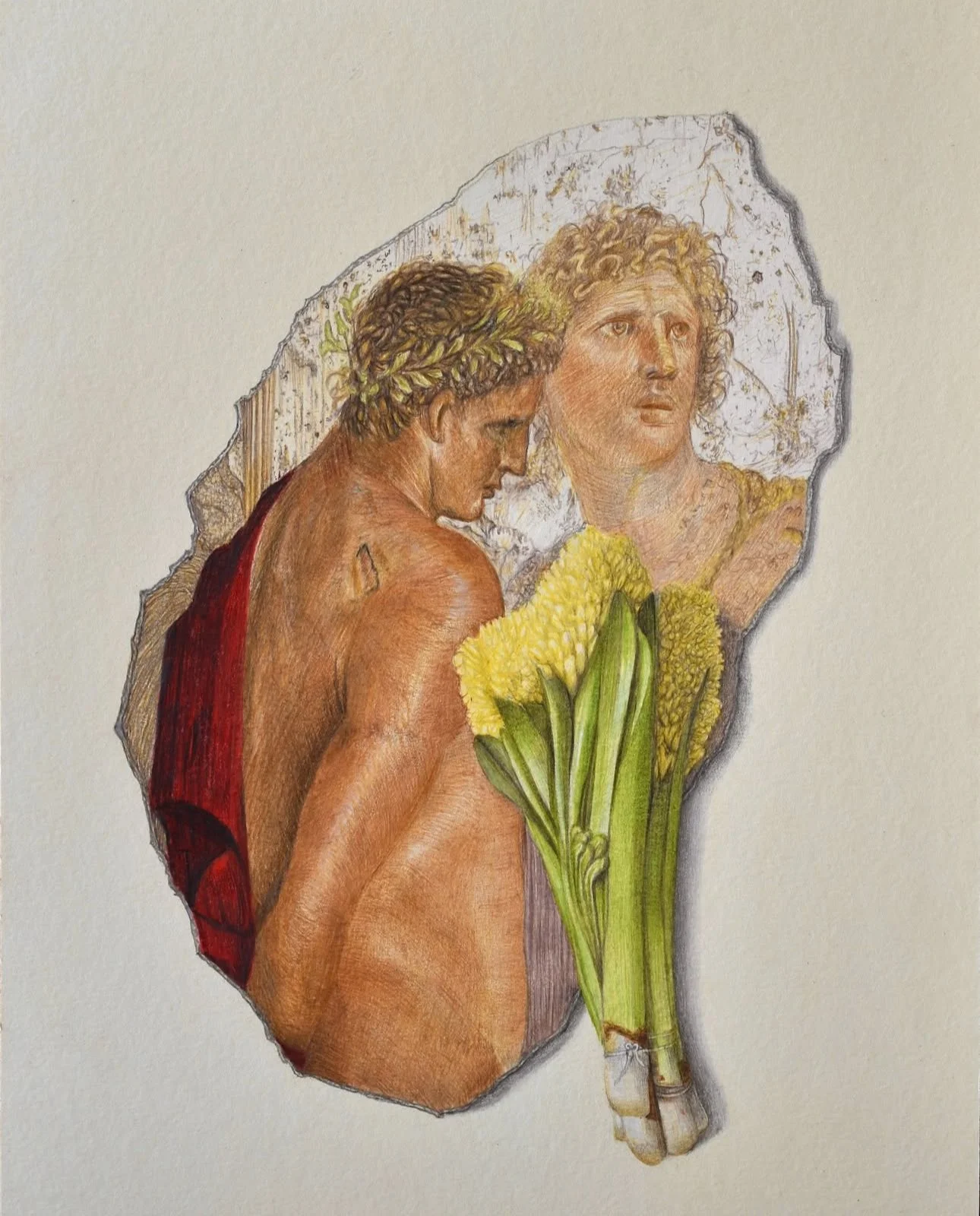

Sometimes breaking off only a single section of an object can serve a different effect: that of narrowly focusing on a scene and thereby telling a different story from the one told in its original setting.

This was the case with a drawing that I created for a group show at Vardan Gallery in Los Angeles. It’s based on a section of a large Roman wall painting I saw when it was on show at the British Museum’s Troy: Myth and Reality exhibition.

It was originally located in the House of the Citharist in Pompeii, and the scene depicts the mythical Greek figure Orestes, his companion Pylades, his sister Iphigenia and the King of Tauris. It’s a moment of tension and high drama as they consider the curse that shapes the hero’s fate. By mentally taking a chisel to this section and laying a bunch of flowers in the space between Orestes and Pylades I wanted to reframe the characters, and move from a scene of imminent action to one of quiet intimacy.

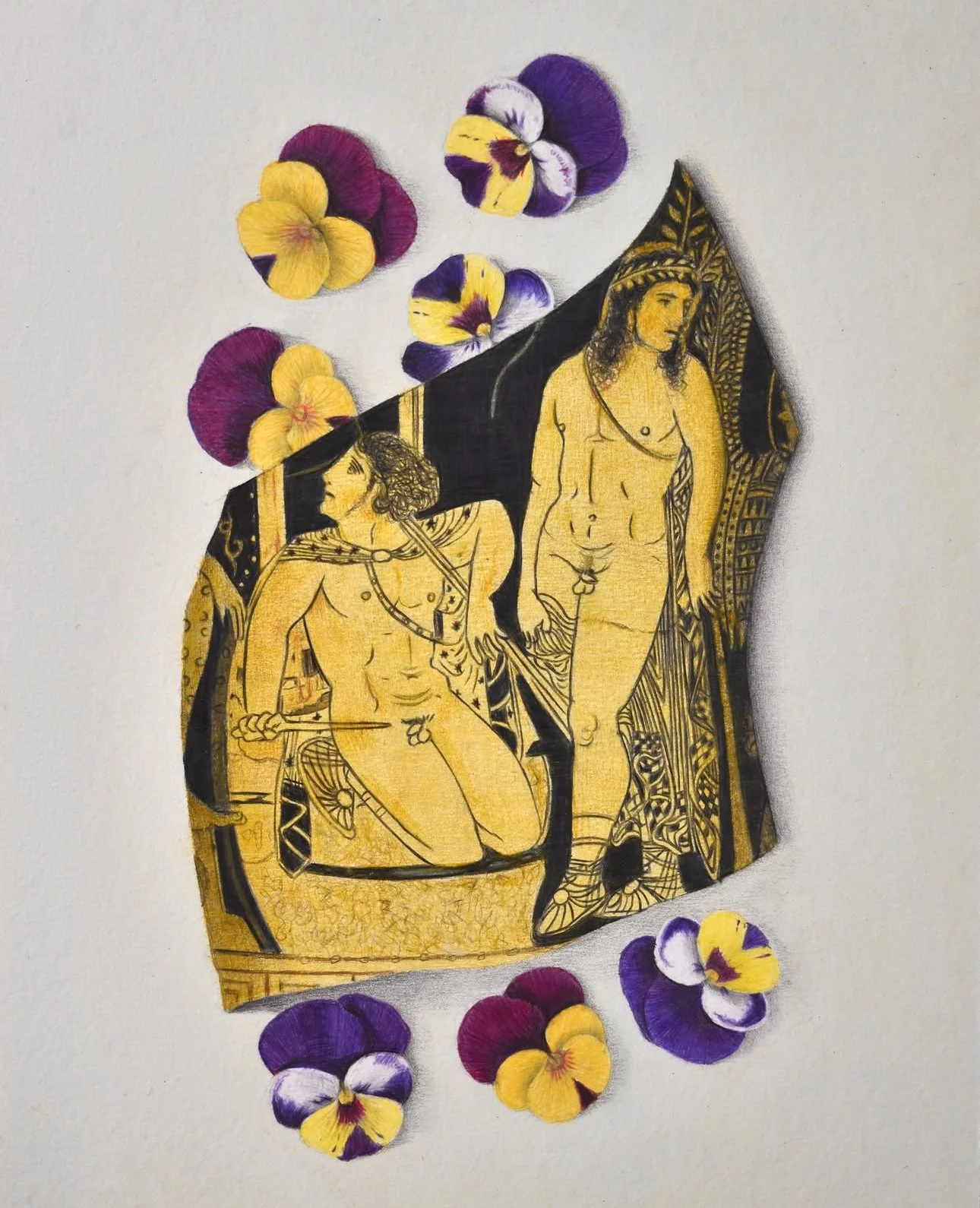

I applied the same thinking to another composition featuring an imaginary fragment of a large vase in the British Museum’s collection.

The vessel is a wine bowl known as a bell-krater, and also (purely by coincidence) depicts Orestes. But this time he’s at the holy sanctuary of Delphi, the most sacred place in the Ancient Greek world. He’s flanked by the gods Athena and Apollo, who grant him purification for the killing of his mother, and thus relief from the Furies (the Greek goddesses of vengeance). By taking a shard containing Orestes and Apollo and placing it over a scattering of pansies, I wanted to detach them from the scene and its tension and make them into an ambiguous pairing.

In this fragment the action of the bigger scene, which is now ‘offstage,’ is implied by their separate gazes, as well as the glimpse of a hand next to Orestes and drapery beside Apollo. But separated from its former context, the story has been broken, and a new one must be told from scratch by viewer.

I didn’t imagine, when I started creating series of still life drawings, that it would be the first step towards an imaginary career as an art vandal. But the greater surprise was how it could open up the hidden potential of the artefacts themselves. In a strange sense they’re like piggy banks, releasing their value in the act of their destruction.