One day several years ago, when I was visiting the Museum of London, I saw an artefact that would plant a seed in my imagination that’s only recently begun to germinate.

It was a seventeenth century white and blue ceramic tankard with stylised nature motifs. It’s a form that’s characteristic of the period, and I’d seen them in museums before. But a particular feature of this one gave me pause. In a band along the centre of its body ran a striking message:

THE GIFT IS SMALL GOODWILL IS ALL.

The beautiful simplicity of the words and their harmony with the design on the tankard was striking. The text and the imagery joined to create a world played out on the surface of the vessel.

My instinctive response was to capture it in a drawing, and it was this that led to my series of black background still life pieces. In this case I paired it with a butterfly and a bunch of pink roses I’d seen at a friend’s house.

But the idea of a message, a piece of text on a ceramic object, stayed with me. Eventually (we’re talking several years later) I decided that I’d create such messages myself and that they would be love poems. There’s a sense of longing that tends to run through love poetry that seems dreamy to me in a way that’s somehow adjacent to the romance of that seventeenth century stoneware.

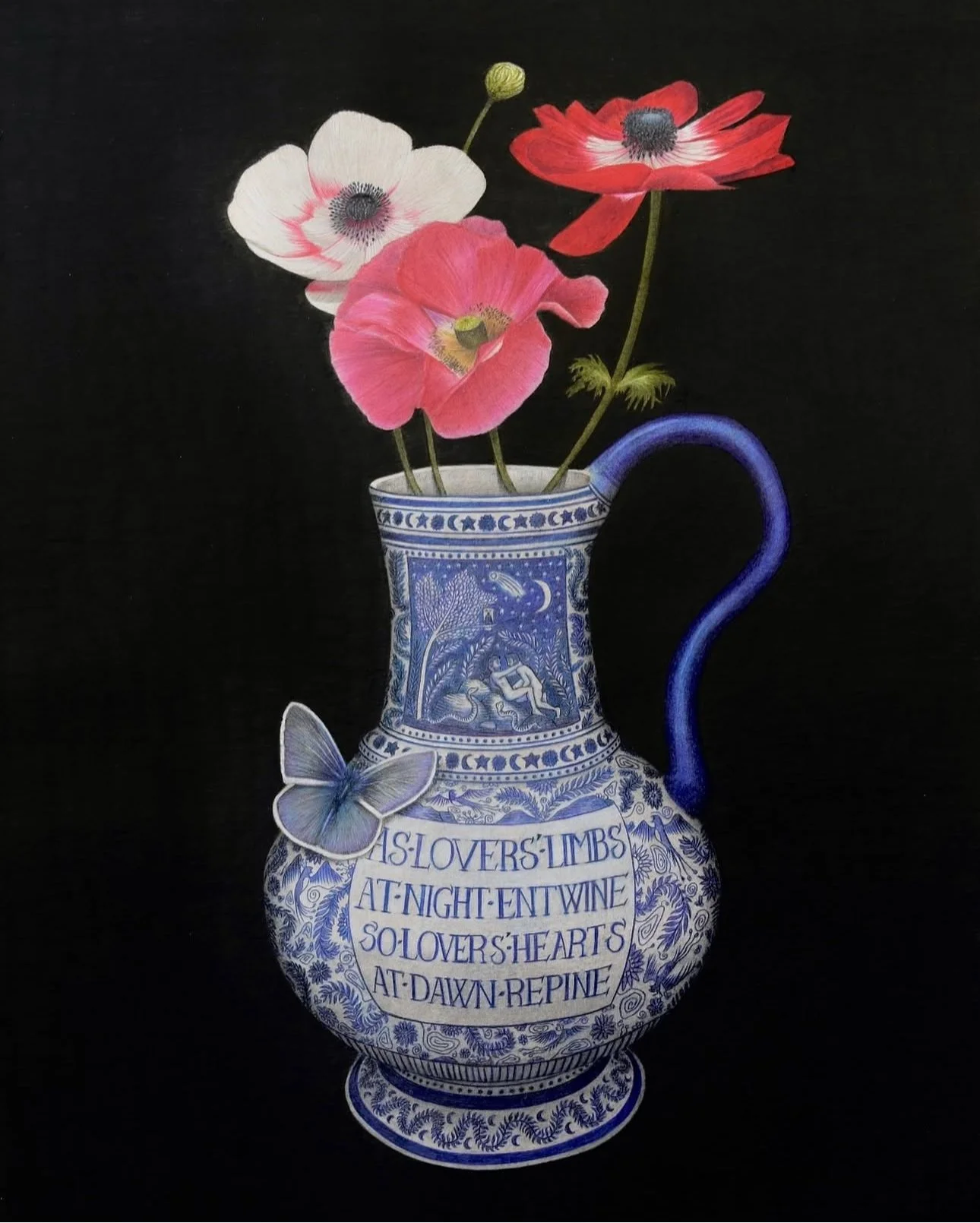

My first composition began with the poem itself:

As lovers’ hearts

At night entwine

So lovers’ hearts

At dawn repine

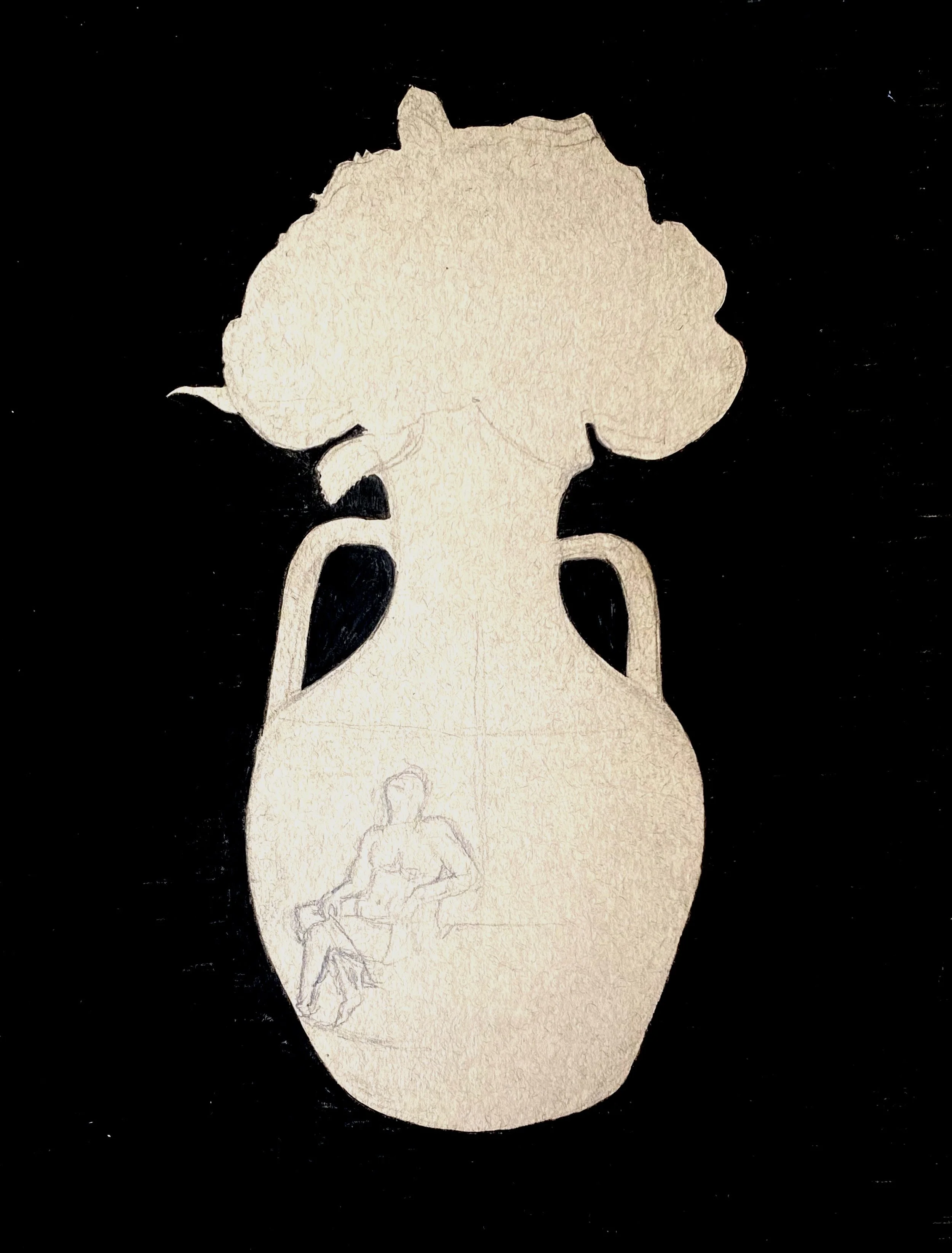

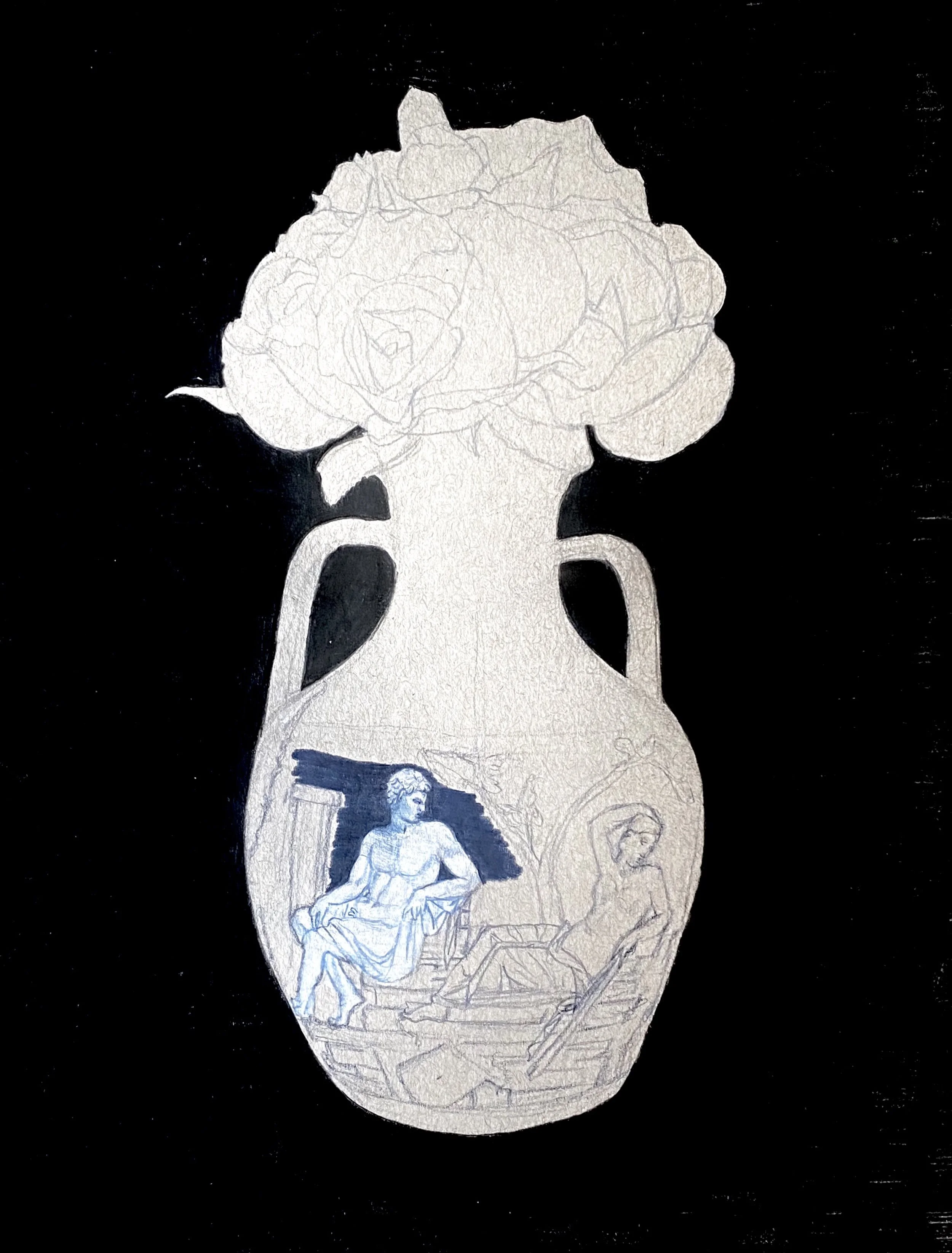

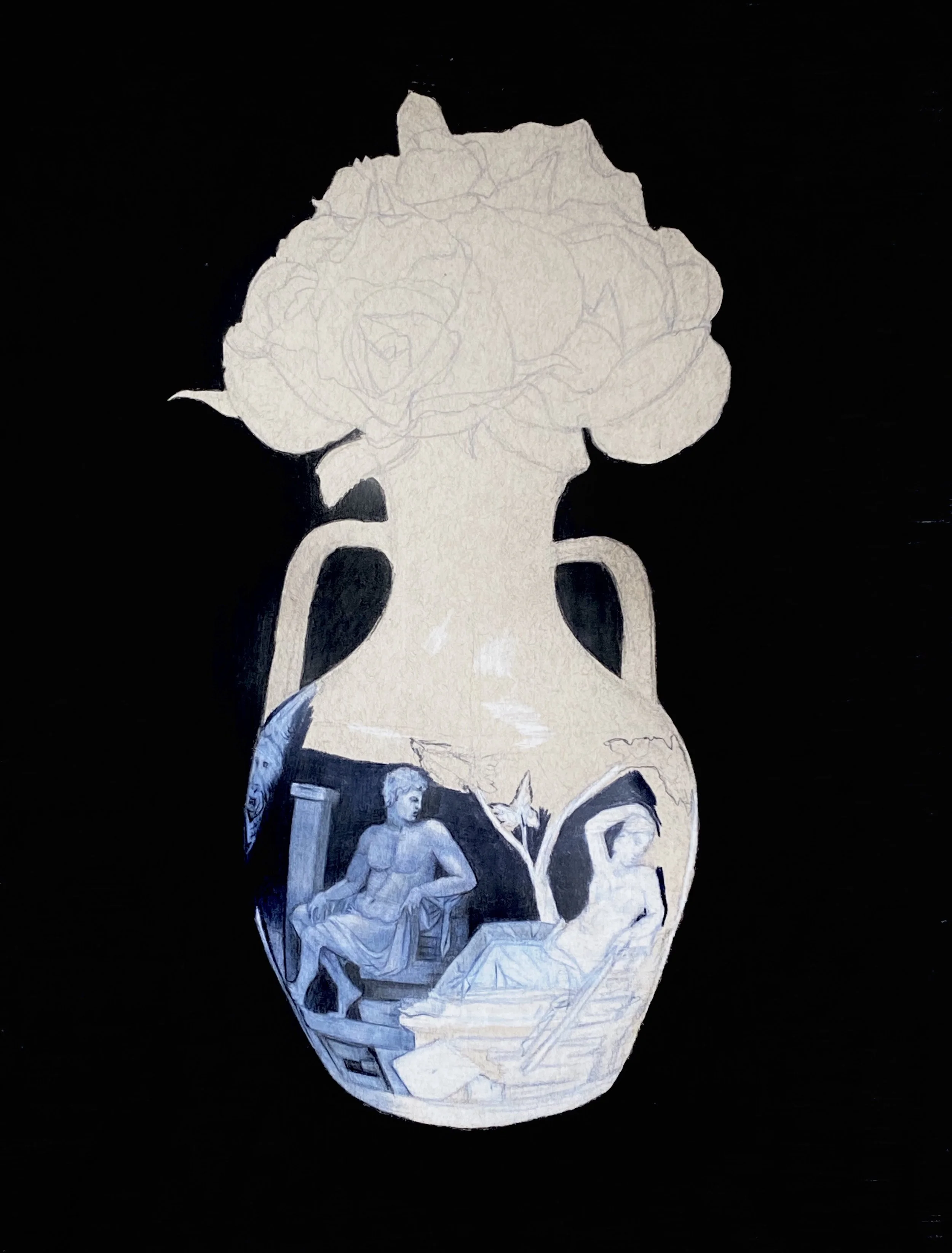

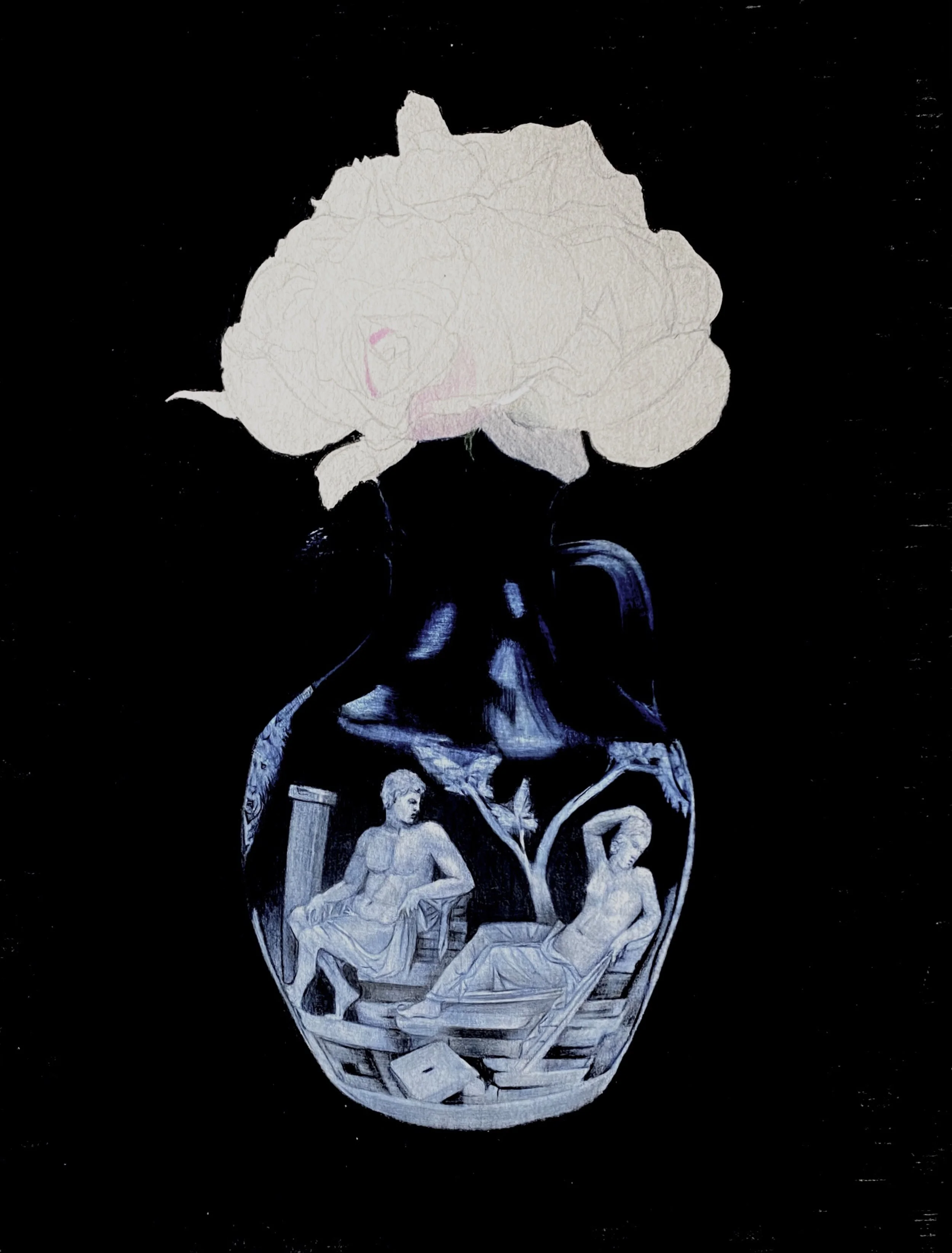

From here I designed the form and decoration of a jug to fit the verse, with twin figures coming together in a moonlit natural setting.

This led to the next piece, again beginning with a poem:

Should your love die

Grass will be my sky

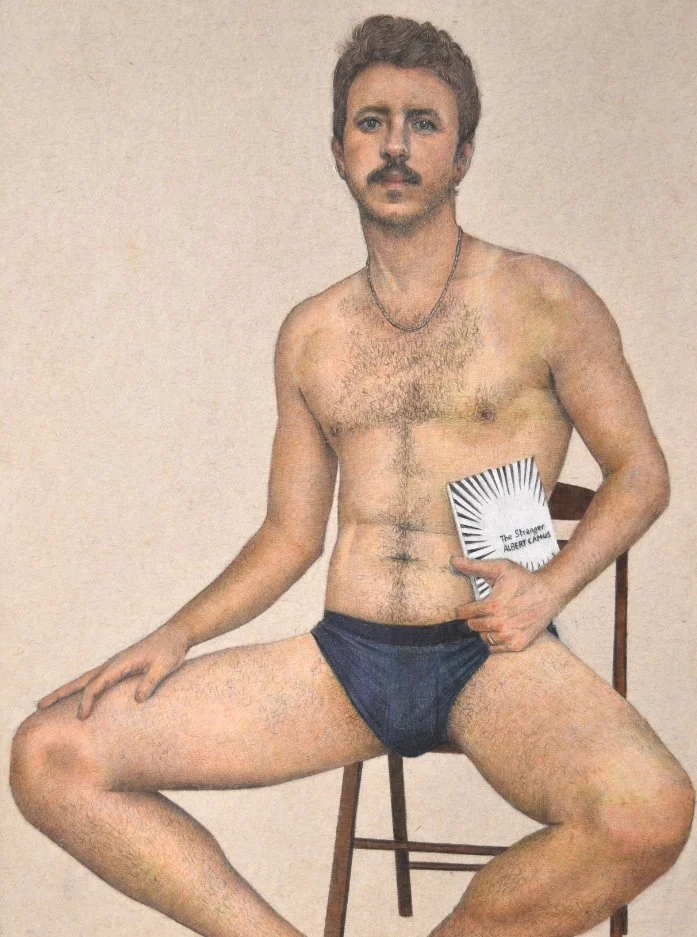

Here I invented a vase with decoration in red and green. And I decided to feature myself this time, appearing as the abandoned lover, physically and symbolically placed below the grass, in the lower section of the vase.

For the third piece I decided to create a painting in oil on egg tempera and acrylic. Again I featured my own portrait. The verse that formed the inspiration for the composition is:

A lover’s gaze

Looks past the pith

And through the glaze

This time I wanted to invert my role in the drama. Whereas previously I was the abandoned lover implied in the poem on the vase, here with the presence of the peeled satsuma it is the viewer who takes on the role of the imaginary lover, looking past the pith of the citrus fruit and through the glaze of the plate.

Now that I have three pieces under my belt I’ve decided to experiment with different ceramic forms. I’m currently working on the next composition, which will feature a pair of invented candle sticks, each bearing one half of a new poem. They really do need to be candle sticks as this directly relates to the text I’ve written. The challenge will be to make it fit comfortably on their surfaces.

I’ll have to put my seventeenth century thinking cap on.